Executive Summary

Background

Commercial and residential buildings are responsible for over 70% of NYC’s greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions (City of New York, 2024). To address the large impact of buildings on climate, New York City’s Local Law 97 (LL97) mandates significant reductions in GHG emissions from large buildings with increasingly stricter caps every five-years. LL97 aims to reduce the emissions from the city’s building sector 40 percent by 2030 and 80 percent by 2050 (New York City Department of Buildings). LL97 is essential to achieving the city’s broader climate goals by accelerating progress and developing strategies to achieve carbon neutrality (New York City Department of Buildings). However, LL97’s implementation poses serious challenges for rentregulated and income-restricted housing, which often lack the financial and technical resources to comply with the law. These buildings typically face aging infrastructure, limited access to capital, and affordability restrictions that limit landlords’ ability to recoup retrofit investments, especially under rent stabilization laws.

To ensure that LL97 implementation does not jeopardize housing stability, this report recommends allowing block-level compliance in low-income areas, establishing tailored timelines for Section 321 properties, and expanding financial support for deep retrofits. Our analysis shows that electrification of space heating with additional envelope upgrades and shared infrastructure will be essential for meeting 2030 targets. These strategies will likely need to be coupled with financing mechanisms and pilot programs to align emissions reduction with housing equity.

Key Findings

- Retrofit Strategies and Compliance

- Electrification of space heating and domestic hot water via packaged terminal heat pumps (PTHP) is sufficient for some compliance scenarios but not for long-term deep decarbonization in most cases. (2.2.5.f. Alternative Scenario 6, Table)

- Envelope upgrades (e.g., improved insulation and window replacements) are critical for emissions reductions, while basic weatherization measures like insulation and air sealing NYC Decarbonization Studio Report 2025 5 are more affordable and widely supported by funding programs, window replacements remain expensive and technically challenging in older multifamily buildings.

- Solar PV installations on individual rooftops yield marginal GHG reductions due to the limited available rooftop area, but shared systems at the block level present a promising supplement. Such community-scale PV systems, which can generate up to 18% more energy than the total load and reduce grid imports by over 50%, offer a scalable pathway to net-zero compliance in urban contexts. (Lane et al., 2024).

- Typology-Specific Insights

- Pre-war and post-war multifamily buildings exhibit different retrofit challenges due to both their heating system design and fuel type. Pre-war buildings often rely on steam-based heat distribution, which is less efficient and more difficult to electrify than hydronic (hot water) or forced-air systems typically found in post-war buildings.

- Building-level strategies (technologies) likely should be paired with targeted financing mechanisms for building owners with low capital reserves or limited tenant rent flexibility.

- Policy Recommendations

- Allow for Block Level Compliance for low-income areas and a tailored compliance pathway for rent-regulated buildings in low- to medium-income neighborhoods.

- The NYC Department of Buildings (DOB) should develop a phased inclusion plan for section 321 Properties and block-level pilot programs for shared infrastructure retrofits (e.g., shared geothermal systems or district-scale solar).

- Incentives should support deep retrofits prioritizing emissions and cost reductions and should be integrated with NYSERDA and federal programs.

Our Study

This report is a product of a graduate urban planning studio class at Rutgers University that investigated the intersection of decarbonization and housing by analyzing LL97’s impact on nonsubsidized affordable housing. To do this, we first determined what decarbonization strategies were most effective for emissions and cost reduction in low-income multifamily buildings and, second, offered suggestions to policymakers on how to structure LL97 implementation in a way NYC Decarbonization Studio Report 2025 6 that promotes compliance without compromising housing stability. We identified retrofit strategies such as electrification, envelope upgrades, and solar installations that align compliance with affordability through spatial, energy, and cost analysis. We also examined opportunities for block-level interventions, like shared renewable energy systems and district heating, which may be more scalable and financially viable for clustered affordable housing. By combining technical modeling with a policy-facing lens, this report aims to support equitable climate action that meets both environmental and social objectives.

Methodology

The study employed geospatial analysis, energy modeling, and policy review. Key steps included:

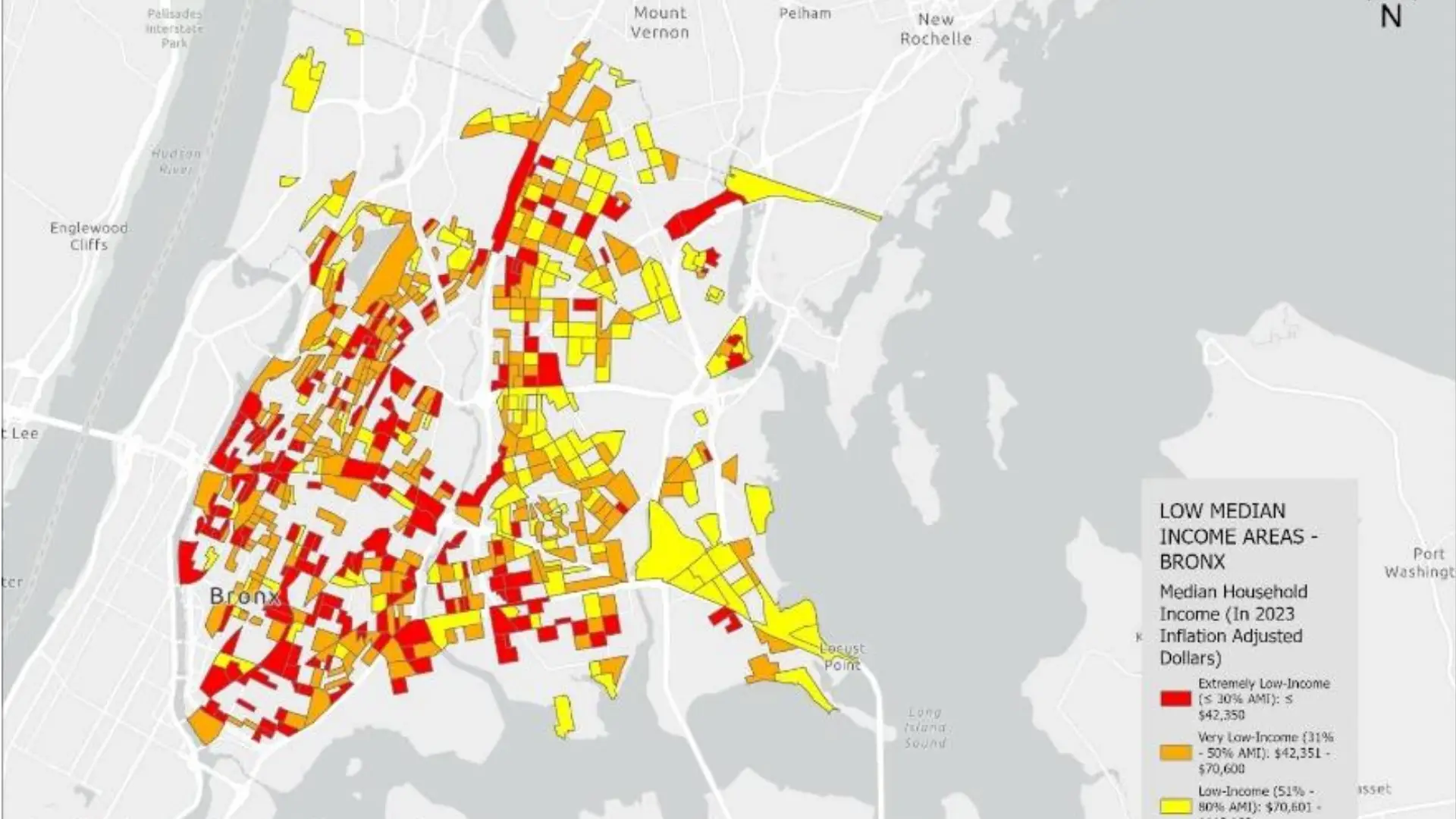

- Mapping rent-regulated housing and LL97 compliance risks using MapPLUTO and Local Law 84 benchmarking data.

- Selecting representative case studies to simulate retrofitting scenarios.

- Estimating emissions and energy use impacts of electrification, envelope upgrades, and solar integration. Using building energy performance simulation modeling tools.

- Evaluating cost to assess feasibility and equity tradeoffs.

Students

Adnan Zia

Annabelle Simhon

Maham Khurshid

Shuhan Lei

Keiya Satoh

Joseph A. Brosnan

Prepared for the New York City Department of Buildings by Ioanna Tsoulou, Liaison